Reading notes: How To Tell When We Will Die

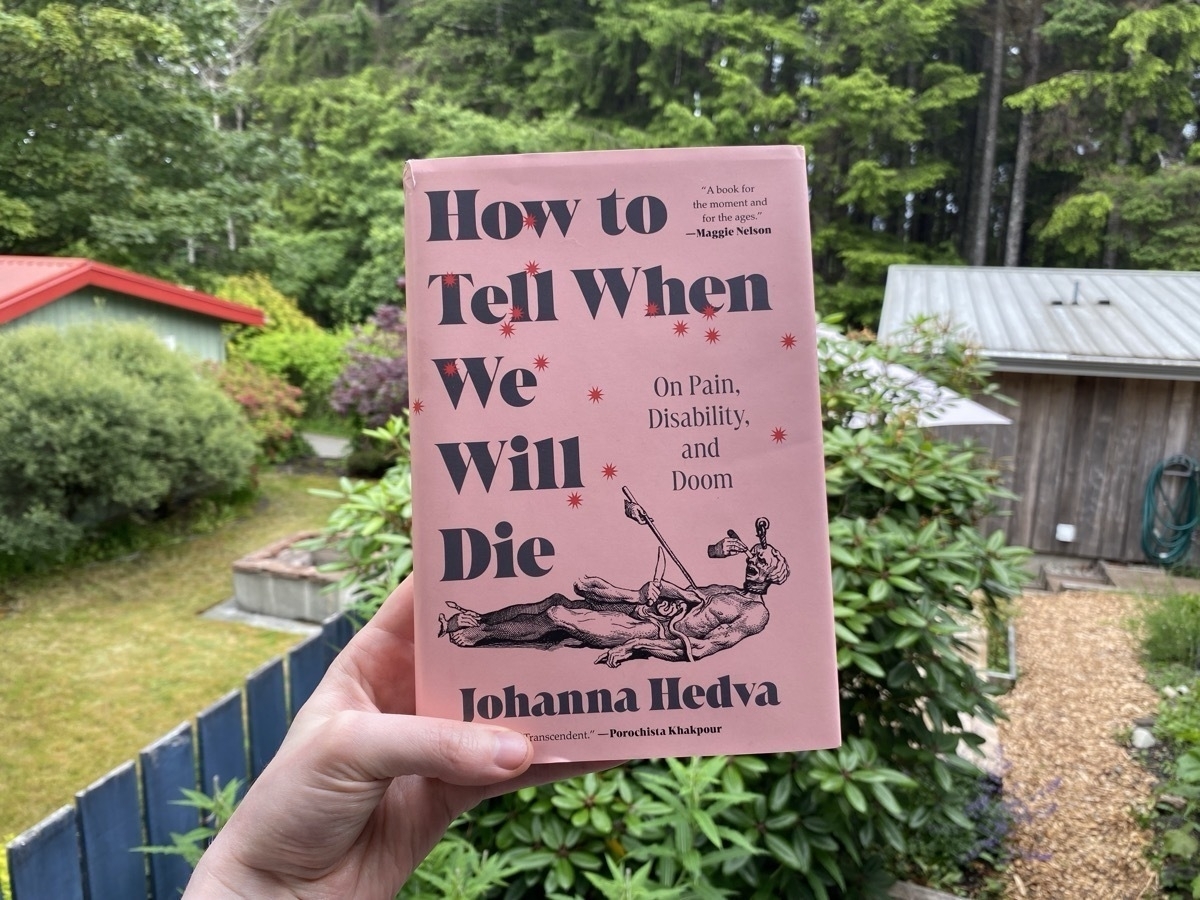

#Lately I’ve been reading How To Tell When We Will Die, a collection of essays by Johanna Hedva. My hardcover copy came from the bookshop at my house (Which 3rd Avenue Books in Daajing Giids), but I couldn’t read very far without wanting to underline everything. So I swiped it.

Now that I’ve finished reading it once through, I’m going back to re-read some of the essays and see what ideas I can hang onto to better understand and be able to advocate for accessibility and disabled people like me.

I’ll be making notes, and you’re welcome to read along the way. Sort of like I did with Against Technoableism last year.

My brain weather is pretty messed up right now, as I’m going through an extended chronic illness flare-up. I’m not sure how long this re-read will take. But I’ll add to this post as I go.

Some overall thoughts

- When I’m unwell, I’m at my most existential. This book indulges me. It gets into the gritty, sloppy mess of what it means to be a human body subjected to late-stage capitalism. What it means to live and die and just look directly at decay and death, which is our uncomfortable common fate. This book helped me see that doom and disability have the potential to become the seeds of love, compassion, care, and courage.

- There’s a dark joke in the disability community online that goes something like this: If you don’t celebrate disability pride month this year, don’t worry. You will one day.

- I don’t expect everyone to study death and disability or to know what it’s like to be disabled. But I do expect better of Western culture and its attitudes toward accessibility. It’s embarrassing that our societies are so desperate to ignore death and treat disability as a taboo. It’s a cringe way to live.

- Entropy is already here, so we might as well help each other out!

1. The title essay: “How To Tell When We Will Die”

Doom generates life.

This piece is part memoir and part disability essay. Hedva is a “queer and gender non-binary second-generation Korean American writer, artist, and musician” from LA. Some notes and quotes that stood out from this first chapter:

Disability and storytelling

- She talks about disability and illness in storytelling and our self-conception: “In order to live, we tell ourselves stories that do not include illness. […] We tell ourselves that our personalities are defined by our brilliance, curiosity, orneriness, and passion, not our panic, brain fog, or fatigue.” (1)

- She asks what would happen if we were to force disability to the forefront of our stories. “What about stories that are enlivened, vivified, not despite illness and disability but because of them?” (5)

- This reminds me of Virginia Woolf’s essay “On Being Ill”, where she laments the way illness is overlooked in literature. Hedva has a similar argument, but also brings it to a personal level. Don’t be in denial.

- It’s also food for thought when writing fiction. e.g. Elizabeth Bear’s “Machine” novel (my writing here), where she treats chronic pain as a normal part of a human story and a place where of course there are support systems. Why wouldn’t there be? Not so much a book about disability as one inclusive of it.

What even is your body?

- My favourite part: “The definition of ‘the body’ that I like most is that it’s anything that needs support.” She shortens this to say that the body is “simply a thing that needs.” (5, emphasis by author)

- Lots of ideas in here about how bodies are so delicate and dependent. “I want to reckon with the twin facts that our bodies are fragile and in need of constant care and support, but that we have built our world as if the opposite were true." (4)

- Hedva says her disability experience has been about “relearning how to understand dependency” (6)

What is ableism?

- She quotes Talila A. Lewis’ definition: “noun: A system of assigning value to people’s bodies and minds based on societally constructed ideas of normalcy, productivity, desirability, intelligence, excellence, and fitness. These constructed ideas are deeply rooted in eugenics, anti-Blackness, misogyny, colonialism, imperialism, and capitalism. The systemic oppression leads to people and society determining people’s value based on their culture, age, language, appearance, religion, birth, or living place, “health/wellness,” and or their ability to satisfactory re/produce, “excel,” and “behave.” You do not have to be disabled to experience ableism.” (12, emphasis by the author)

- “The public understanding of terms like “disability” is still the medical model, that it is a body impaired and malfunctioning that requires course-correction.” (13) Against Technoableism is very much about this idea.

- She says the “dis” part of disability is what makes it political. The examination of who has the power and who can be “self-sufficient” in this system. Euphemisms like “differently abled” are not welcome.

What does ableism do for us?

- It provides the illusion of control over our bodies.

- It allows people to ignore death.

- “Ableism protects us from the most brutal truth: that our bodies will disobey us, malfunction, deteriorate, need help, be too expensive, decline until they finally stop moving, and die. Ableism is what lets us believe that this doesn’t have to be true, or at least, that we can forestall it, keep it at bay, and that this is based entirely upon our own will.” (16)

- How can we take away that security blanket?, she wonders. It’s a bit cruel, maybe? But necessary.

Disability, doom, and death

- “Death is fast. Doom is slow.” (21)

- Responding to the ableist idea that disability is a fate worse than death: “Since disability and illness are the most universal facts of life, aren’t they the only fates?” (21)

- Core idea of this book: Doom is place that generates life. “I bring doom into the conversation to show that it is a place to begin, not to end. Once I started thinking of doom as liberatory, I felt free from the dread it constitutes when it looms in the future.” (27)

- A general call to action: “How privileged are you if you first require hope in order to act?” (27)

Misc.

- Hedva wrote an essay called “Sick Woman Theory” in 2014. This went viral and became the centrepiece for writing this book.

- She’s got an interesting POV on writing: Says she writes to find out what is possible to think, rather than to find out what she thinks already. And she wants to find out what thinking can do “when it coexists with the incoherence of a day soaked in pain” (24)

Oh, and as for the title. When will we die? We’re doing it all the time.